Abstract

The full potential for research to improve Aboriginal health has not yet been realised. This paper describes an established long-term action partnership between Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs), the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AH&MRC), researchers and the Sax Institute, which is committed to using high-quality data to bring about health improvements through better services, policies and programs. The ACCHSs, in particular, have ensured that the driving purpose of the research conducted is to stimulate action to improve health for urban Aboriginal children and their families.

This partnership established a cohort study of 1600 urban Aboriginal children and their caregivers, known as SEARCH (the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health), which is now having significant impacts on health, services and programs for urban Aboriginal children and their families. This paper describes some examples of the impacts of SEARCH, and reflects on the ways of working that have enabled these changes to occur, such as strong governance, a focus on improved health, AH&MRC and ACCHS leadership, and strategies to support the ACCHS use of data and to build Aboriginal capacity.

Full text

Background

Successive governments have committed to closing the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal life expectancy1, and recognised the potential value of research in informing policies, progams and service delivery to improve Aboriginal health.2 However, in practice, research has not always yielded real benefits for Aboriginal people.3

Aboriginal leaders have called for a different approach, in which communities are partners and leaders in research that contributes more directly to improving health.4–6 The National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia has echoed this in its “Roadmap for Indigenous health research”.7 Dr Pat Anderson, former Chair of the Lowitja Institute and an Alyawarre woman from the Northern Territory, stated that:

Decades of research carried out by non-Aboriginal researchers, based in non-Aboriginal institutions, had left many of us deeply suspicious of the ‘r’ word … The research agenda was set in forums to which few of us had access. There were few Aboriginal researchers. And research methodology was still focused on Aboriginal people as subjects of research; research was something carried out ‘on’ us as Aboriginal people, not ‘with’ us and certainly not ‘by’ us. Worse still, despite the large volumes of research to which we were subjected, very little seemed to be translated into practice; the research projects came and went, but health service delivery and policy remained the same.8

The Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AH&MRC) has a long history of leading debate and reform about research in Indigenous communities and, in 2003, joined the Sax Institute to establish the Coalition for Research to Improve Aboriginal Health (CRIAH).9 With inaugural Chair Frank Vincent, CRIAH’s goal was to strengthen partnerships between researchers and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs), and to develop research that improves health policy, programs and services. As one of its first initiatives, CRIAH brought together researchers and ACCHSs to consider priorities for research. At the suggestion of Pat Delaney (a leader in Aboriginal mental health), it was agreed that a long-term cohort study would be established to understand and act upon the causes of health and disease in Aboriginal children in New South Wales (NSW).

The Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH) was the outcome and is a partnership between the AH&MRC, the Sax Institute, researchers and four ACCHSs. SEARCH focuses on Aboriginal children who live in urban areas, since little is known about their health10 and 75% of NSW Aboriginal people live in urban centres.11

About 1600 children and their caregivers have joined SEARCH from four ACCHSs in urban and large regional areas in NSW: Sydney West Aboriginal Health Service (Mount Druitt), Tharawal Aboriginal Corporation (Campbelltown in suburban Sydney), Riverina Medical and Dental Aboriginal Corporation (Wagga Wagga) and Awabakal Ltd (Newcastle). At Newcastle and Wagga Wagga, only families living in the urban and inner regional areas have been recruited. Self-report and clinical measures are collected from children and their caregivers (with details reported elsewhere).e.g. 12–14 The first wave of data collection was completed in 2012; the second is scheduled for completion in 2016.

This paper provides some examples of the impact of SEARCH, and reflects on the ways of working that have underpinned its partnerships and capacity to bring about change.

SEARCH: a long-term platform for closing the gap

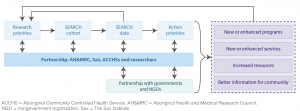

From its inception, SEARCH was envisioned as a new kind of action partnership between researchers and ACCHSs that was committed to using data to drive health improvements. The SEARCH model has matured and evolved during the past decade (Figure 1). The term ‘action partnership’ describes our focus on using data to bring about health improvements through better services, policies and programs. The partnership between researchers and the community-controlled health sector lies at the heart of SEARCH, and drives the identification of priorities, the collection and interpretation of data, and, most importantly, improvements in services, policies and programs. The ACCHSs, in particular, have ensured that the driving purpose of the research conducted is to stimulate action to improve health for urban Aboriginal children and their families.

Figure 1. The SEARCH action model

The SEARCH partnership has increasingly contributed to significant improvements in services and policies, as evidenced by examples in three main areas.

Example 1: enhanced ACCHS services

SEARCH data are being used by participating ACCHSs in the following areas:

- Service focus and policies. All of the ACCHSs have used the data to stimulate dialogue at management and team levels, and to develop targeted improvements in service delivery. For example, in one ACCHS, SEARCH data contributed to an increased focus on asthma, and a review of its existing plans and targets for improved mental health. This was in response to SEARCH data showing that about one-third of the children attending the ACCHS were at risk of emotional and behavioural problems. Similarly, SEARCH data on the rates of overweight and obesity among Aboriginal children and adults prompted a review of current food policies in one of the ACCHSs, and measures were put in place to facilitate healthy eating by staff and preschool children attending child care within the service.

- Information for communities. The ACCHSs use the data from SEARCH to inform their community about health. For example, SEARCH documentation about the high rates of recurrent ear infections was useful to one service in strengthening its existing work in ear health by developing online and print resources based on a cartoon character known as L’il Mike, to engage children and their parents.15 SEARCH data showed that only about half of the children were breastfed, half of their caregivers were smokers, and overweight and obesity was highly prevalent among children and caregivers. These data resulted in another service designing a program to empower women, particularly the Elders, to provide leadership to children and young girls in their communities in health, including discussions about breastfeeding, healthy eating, exercising and reducing smoking. The ACCHS initially engaged with older women in the community to address poor lifestyle choices and habits adversely affecting the health of women and their children. This was followed by regular health promotion training workshops for women targeting key areas where change is needed.

- Submissions for new resources. SEARCH data on smoking and obesity rates in adults (as previously mentioned), and high levels of speech and language impairment in children have been used to demonstrate the need for improved services in funding submissions. In one ACCHS, the submission resulted in a grant of $1 million for smoking cessation programs. In two other services, the SEARCH data were instrumental in attracting funds for a speech pathologist.

- Influencing other agencies. The ACCHSs have used SEARCH data to inform other agencies to provide better care for Aboriginal children. One ACCHS has used the data in discussions with the local Aboriginal Education Consultative Group and the NSW Department of Education to highlight challenges faced by Aboriginal children and to help teachers consider how best to support Aboriginal children at school. Using the SEARCH data that show high rates of skin infections, one ACCHS successfully advocated for a skin check to be included in the primary school health check for Aboriginal children in its region.

In a complex environment, SEARCH can only be one of many drivers of change, but ACCHS Chief Executive Officers nominate the SEARCH data as important:

As a result of the study data, we have redesigned the whole model of care in our mums and bubs program. We have moved from a midwife-led model to one where GPs [general practitioners] and Aboriginal health workers are working together to focus on the main health issues highlighted among the kids – overweight and obesity, ear health and asthma. (ACCHS CEO)16

Example 2: enhanced access to specialist clinical services

SEARCH data showed that about 50% of participating children aged 7 or under had a speech and/or language impairment, and about 30% had middle ear disease14, with potentially serious long-term impacts on health, education and social integration.17,18

SEARCH partners have established long-term relationships with government, and used formal and informal opportunities to draw attention to the findings about ear health and speech. As a result, the NSW Ministry of Health provided $2.3 million over 3 years to undertake the Hearing, Ear Health and Language Services (HEALS) program to facilitate provision of specialist services for children attending participating ACCHSs. SEARCH data were important in demonstrating the need for funding. Equally important was the infrastructure embodied in the SEARCH partnership, enabling rapid provision of the required services. For example, the SEARCH partnership had:

- Aboriginal research officers at the ACCHSs with the skills and community trust to support families to use the services

- Close working relationships with the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, which provided overall governance, management and coordination of the program to ensure the timely delivery of services

- Established links with speech therapists, and ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeons to provide services.

The new funds provided care to 790 Aboriginal children, including an extra 6175 occasions of care with speech–language pathology services, and 224 ENT surgeries. It eliminated waiting lists for speech and language therapy at all participating ACCHSs, and waiting lists for ENT surgery were eliminated at three out of four services. Most importantly, improved outcomes for children were reported:

Especially the parents, they’d be saying, oh the teachers are saying he’s doing so well now. He’s actually paying attention in class and having input in class instead of sitting in the back because he doesn’t know what’s going on, he can’t hear. (Aboriginal health worker)19

K has been speaking a lot more in class compared to before. Before, when people couldn’t understand him, he would walk away, but apparently he tries really hard to get his message across now! (Parent/caregiver)20

This work is now being extended to estimate the costs, health benefits and potential social outcomes of a sustainable expanded program to cover all of NSW.

Example 3: improved environments

Poor housing has been repeatedly identified as a major cause of ill health by ACCHSs and SEARCH participants. In contrast to rural and remote areas21, little is known about housing issues for urban Aboriginal people. In qualitative data, SEARCH participants described how housing experiences were materially affected by their Aboriginality. They reported difficulty accessing housing, secondary homelessness, overcrowding and poor dwelling conditions.22 Issues reported included damp and mould, major structural problems, vermin, crowding, poor dwelling security, and affordability problems.23

NSW Health has a long-standing innovative Housing for Health program that uses a structured approach to improve Aboriginal community housing stock primarily in rural and remote areas.24 Data from SEARCH have demonstrated the high level of concern about housing and its impact on health among Aboriginal people living in urban areas, where many Aboriginal people live in public housing rather than that owned by Aboriginal housing organisations. NSW Health has recently implemented the Housing for Health program in families attending one of the SEARCH ACCHSs.

The SEARCH model: what has worked to drive change

The previous three examples illustrate some of the many changes to services and programs stimulated by the SEARCH partnership. SEARCH has required a long-term commitment to a shared endeavour by researchers, the AH&MRC, ACCHSs and the Sax Institute. It has, in turn, built the trusting partnerships that ought to underpin evidence to improve health in this sector. It has been able to give the time required to enable the partners to understand each other’s perspectives, so that, gradually, truly shared goals have emerged and a platform for change was created. This has not always been easy, and all of the partners have adjusted their ways of working to enable the partnership to succeed. Some ways of working have been particularly important in achieving outcomes:

- Strong governance. At its inception, formal memorandums of understanding (MOUs) were put in place to provide a framework for the SEARCH program’s governance. The MOUs described the principles under which SEARCH was established, including Aboriginal leadership in the program, partnership approaches to decision making and a focus on achieving health outcomes for children and their families. The MOUs also established the mechanisms to deliver on these principles, such as ACCHS representation as chief investigators on funding applications; regular decision-making forums with ACCHS Chief Executive Officers, including agreement to any new directions; approaches to publication of the data, including an Aboriginal-led data access and publication committee; and ACCHS employment and supervision of the Aboriginal research officers.

- Explicit focus on using the data to improve health. The key objective of SEARCH has always been to improve the health of urban Aboriginal children and their families. This principle has remained at the forefront of dialogue, and strategies are in place to operationalise this commitment. For example, throughout data collection, study investigators, including paediatricians, held monthly teleconferences to review the individual data and to support appropriate referral of children if required. Early on, it became apparent that additional speech pathology services were required, and they were sourced by the wider SEARCH team. As shown in Figure 1, the SEARCH team used its collective networks to ensure that organisations such as the NSW Ministry of Health, the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network and beyondblue were engaged in helping to support improved services and programs. The leadership by the ACCHSs and the AH&MRC in maintaining the focus on health benefits has been particularly important.

- AH&MRC and ACCHS leadership. SEARCH would not have been possible without strong leadership from the ACCHSs. The ACCHSs have directed the priorities and advised on the way in which data could be appropriately collected within their communities. Their ownership of, and advocacy for, SEARCH has been critical to the capacity to recruit families to a long-term research program, and has enabled SEARCH to be known and valued by communities. In the follow-up phase, local community knowledge has enabled the location of children for invitation to follow-up. ACCHSs expertise ensures the implications of the data are understood, and that change occurs at the service and local levels.

- Strategies to support ACCHSs’ use of the data. SEARCH has rich data about 400 children from each ACCHS, which are provided to the ACCHS in tabular and unit-record formats. The study statistician is available to undertake special-purpose analyses for the ACCHSs. SEARCH employs an Aboriginal knowledge broker who has strong links with the ACCHSs, and has the skills and capacity to bring key people together to share research findings in an easily understood format. The Aboriginal knowledge broker, who is very familiar with the SEARCH data and with the ACCHS sector, regularly meets with each ACCHS to help it to identify the key issues for its service and what might be the implications for action. A major forum is held each year to consider the emerging analyses and potential future directions. Local feedback is provided on a regular basis as advised by the ACCHSs. ACCHS staff have been part of drafting the study papers, increasing the likelihood that the data will be owned, understood and used locally; this approach has also enriched the wider study team’s understanding of the data and its implications.

- Building Aboriginal research capacity. SEARCH has had a core commitment to supporting the development of research capacity among the Aboriginal research officers at each ACCHS and Aboriginal staff in the coordinating centre. Four of these staff have or are pursuing formal higher education in research. Training in research methods and in paper writing has been provided for all of the Aboriginal research officers, and these staff have presented at conferences12,25 and contributed to papers for peer-reviewed journals.

Conclusions

From its inception, SEARCH was envisioned as a new kind of action partnership that would generate and use data to improve the health of urban Aboriginal children. Ten or so years after its establishment, SEARCH can point to many examples of improved services and programs as the result of its work. The capacity to bring about change has been driven by partnerships between the AH&MRC, the Sax Institute, ACCHSs and researchers. Government, particularly NSW Health, has been a key contributor. Sometimes, several changes to address the same health issue have occurred at different levels – for example, the additional funds for ear surgery and the L’il Mike program should work synergistically to improve ear health in participating children. These changes have been driven using varied and innovative approaches by the SEARCH partnership, are ACCHS owned and are incremental. Our experience suggests that long-term partnerships such as SEARCH may be particularly effective in bringing about improvements in Aboriginal health.

Acknowledgements

We thank the SEARCH participants, their communities and the staff at participating ACCHSs. This work was supported through grants to SEARCH from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant numbers 358457, 512685, 1023998 and 1035378), the NSW Ministry of Health, the Australian Primary Care Research Institute, beyondblue and the Rio Tinto Aboriginal Fund. SEARCH is conducted in partnership with the AH&MRC and four Aboriginal medical services across NSW: Awabakal Limited, Riverina Medical and Dental Aboriginal Corporation, Sydney West Aboriginal Health Service, and Tharawal Aboriginal Corporation.

Copyright:

© 2016 Wright et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence, which allows others to redistribute, adapt and share this work non-commercially provided they attribute the work and any adapted version of it is distributed under the same Creative Commons licence terms.

References

- 1. Australian Government. Closing the gap: Prime Minister's report 2010. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2010 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: generationone.org.au/uploads/assets/closingthegap2010.pdf

- 2. Australian Government. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2013 [cited: 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/B92E980680486C3BCA257BF0001BAF01/$File/health-plan.pdf

- 3. Thomas D, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Changing discourses in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research 1914–2014. Med J Aust. 2014;201(1):S15–S8. CrossRef | PubMed

- 4. Mundine K, Edwards L, Williams JDB. Why an Aboriginal ethical perspective is necessary for research into Aboriginal health. Sydney: Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of New South Wales; 2001 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.ahmrc.org.au/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=22&Itemid=45

- 5. Todd AL, Frommer MS, Bailey S, Daniels JL. Collecting and using Aboriginal health information in New South Wales. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(4):378–81. CrossRef | PubMed

- 6. NSW Aboriginal Health Resource Co-Operative Ltd, NSW Department of Health. NSW Aboriginal Health Information Guidelines. Sydney: Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council; 1998 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.ahmrc.org.au/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=22&Itemid=45

- 7. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research Agenda Working Group of the NHMRC. The NHMRC road map: a strategic framework for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health through research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2002 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/r28.pdf

- 8. Anderson P. Keynote address: research for a better future. Coalition for Research to Improve Aboriginal Health 3rd Aboriginal Health Research Conference. Sydney: Lowitja Institute; 2011 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.lowitja.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/Pat_Anderson-CRIAH-27_04_2011.pdf

- 9. Sax Institute. CRIAH – the Coalition for Research to Improve Aboriginal Health. Sydney: Sax Institute; [cited 2016 May 2]. Available from: www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/criah/

- 10. Eades S, Taylor B, Bailey S, Williamson A, Craig J, Redman S. The health of urban Aboriginal people: insufficient data to close the gap. Med J Aust. 2010;193(9):521–4. PubMed

- 11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Healthy for life – Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services report card. Canberra: AIHW; 2013 [cited 2016 May 5]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129543587

- 12. The SEARCH Investigators. The Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH): Study Protocol. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:287. CrossRef | PubMed

- 13. Reed R, WIlliams S. The Study of Environment of Aboriginal Child Health (SEARCH): preliminary findings. Primary Health Care Research Conference. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research and Information Service; 2015 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.phcris.org.au/phplib/filedownload.php?file=/elib/lib/downloaded_files/conference/presentations/8179_conf_abstract_.pdf

- 14. Gunasekera H, Purcell A, Eades S, Banks E, Wutzke S, McIntyre P, et al. Healthy kids, healthy future: ear health, speech and language among urban Aboriginal children (the SEARCH study). J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47(Suppl 2):6. CrossRef

- 15. Awabakal. L'il Mike: healthy ears = deadly kids! Newcastle: Awabakal; 2015 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.awabakal.org/lil-mike

- 16. Gordon R. CEO Update: Awabakal. Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH) Annual Forum 2015; Sydney.

- 17. Williams CJ, Jacobs AM. The impact of otitis media on cognitive and educational outcomes. Med J Aust. 2009;191(9):S69. PubMed

- 18. Walker N, Wigglesworth G. The effect of conductive hearing loss on phonological awareness, reading and spelling of urban Aboriginal students. Aust N Z J Audio. 2007;27(1):37–51. Article

- 19. Gunasekera H, on behalf of HEALS team. Hearing Ear Health and Language Services (HEALS): An innovative project providing ENT and Speech therapy for Aboriginal Children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51(Suppl 2):5–6. CrossRef

- 20. Sax Institute. Realising possibilities: annual report 2012–2013. Sydney: Sax Institute; 2013 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/SAX15176-Annual-Report-2811_WEB.pdf

- 21. Torzillo PJ, Pholeros P, Rainow S, Barker G, Sowerbutts T, Short T, et al. The state of health hardware in Aboriginal communities in rural and remote Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(1):7–11. CrossRef | PubMed

- 22. Andersen M, Williamson A, Fernando P, Redman S, Vincent F. "There's a housing crisis going on in Sydney for Aboriginal people": focus group accounts of housing and perceived associations with health. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):429. CrossRef | PubMed

- 23. Andersen M, Williamson A, Fernando P, Wright D, Redman S. Urban Aboriginal housing conditions: tenure type matters. Proceedings of the Australasian Housing Researchers Conference; 2016 Feb 17–19; Auckland. p. 72. Available from: cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/creative/schools-programmes-centres/URN/documents/AHRC2016-Handbook-FINAL.pdf

- 24. Aboriginal Environmental Health Unit. Closing the gap:10 years of housing for health in NSW. North Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2010 [cited 2016 May 27]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/environment/Publications/housing-health.pdf

- 25. Sherriff S, King J. The perspectives of urban Aboriginal people on access to child ear health and speech services: Hearing, EAr health & Language Services (HEALS) project. Primary Health Care Research Conference. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research and Information Service; 2015 [cited 2016 Jun 28]. Available from: www.phcris.org.au/resources/item.php?id=8204&spindex=3